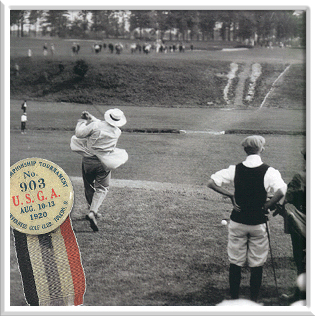

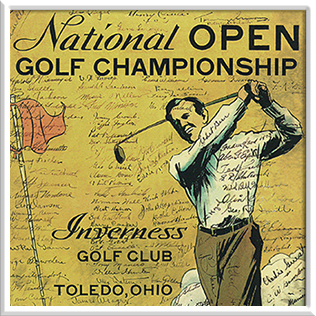

The first major championship played at Inverness Club took place in 1920 when the Donald Ross course was in its infancy. Present-day golf fans know Inverness Club for the thrilling finishes in the 1986 and 1993 PGA Championships. The first major at Inverness Club was no different.

Harry Vardon, a seven time major champion and the most dominate player of the time, was the favorite. He held a five stroke lead with five holes to play. However, he faltered with three putts on three holes on the back nine. Ted Ray of Great Britain managed to win by a single stroke over a foursome of runners-up that included Jock Hutchison, Jack Burke, Leo Diegel, and Harry Vardon.

The top finishers, including an eighteen year old amateur from Georgia playing in his first U.S. Open, Bobby Jones, and the rest of the record-286-man field were welcomed with open arms into the Inverness clubhouse. This was the first time the members of a private club opened their doors to participants. Every club since has carried on this gesture. The players so appreciated the hospitality of the club that they pooled their funds to purchase a cathedral clock as a gift for Inverness Club members.

Thus, as Ray made history, so did Inverness Club. Although that first Open at Inverness occurred more than eight decades ago, the cathedral clock presented to the Club by grateful competitors still stands in the clubhouse lobby, and the memory and spirit of the 1920 U.S. Open lives on.

Read more...

In 1931, Inverness Club hosted the U.S. Open for the second time. Once again, Inverness played a significant role in the history of championship golf. This championship featured many firsts, and an important last. The 1931 U.S. Open was the first to be won by a player using steel shafted clubs. It was the first to be nationally broadcast – on radio, of course. Also, the “American” golf ball, measuring 1.68 inches in diameter debuted at the 1931 U.S. Open; now the game’s standard. But, this Open is most remembered for being the longest in major golf history. It took 144 holes to settle – eight rounds of golf. The USGA installed the 18-hole playoff after this tournament, which remains the format to present day.

The tournament came down to a contest between a former amateur standout whose status was somewhat murky and a little known club professional. That duo, George Von Elm and Billy Burke, played an unprecedented 144 holes in an early-July heat wave, before the championship was determined. They played the equivalent of two full tournaments.

The scheduled three days of play featured eighteen-hole rounds on July 2nd and 3rd with a thirty-six hole finish on Saturday July 4th. After four rounds, Burke and Von Elm were tied at 4-over 292. Von Elm, a first-year pro who had stunned Bobby Jones in the finals of the 1926 U.S. Amateur at Baltusrol in New Jersey, forged the tie with a ten-foot putt on the final hole, thereby forcing a thirty-six hole playoff on Sunday. The next day, was nearly a repeat, with Von Elm getting a birdie on the final hole to force a second 36-hole playoff. Burke won by one shot, after the second 36-hole playoff, to win the marathon championship.

Read more...

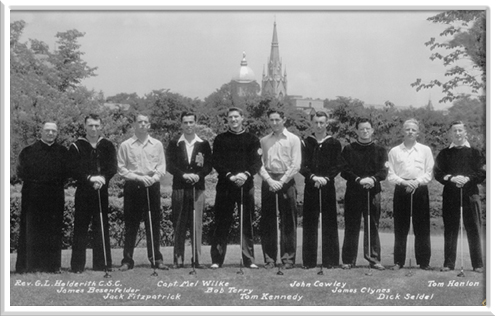

Played in late June 1944, the NCAA Championship came to Inverness Club just three weeks after Allied Forces launched Operation Overlord. Over 160,000 troops landed on the beaches of Normandy, and thousands perished in bloody fighting that would mark the beginning of the end of World War II.

As it did in every part of our lives, the war effort also took its toll on golf and the NCAA Championship in particular.

The defending team champion was Yale University, which had won an incredible 21 titles (out of a total of 46 championships) from 1897 to 1943. But travel restrictions forced the Bulldogs to stay at home. Yale never won another title.

Other teams and players were similarly affected. A field of only 50 players or so entered the event, and most were from the Midwest. Because of the uncertainty with travel plans, entries were accepted on the tee for the first round. Teams from Kent State, Minnesota, Michigan State, North Carolina, Ohio State, Northwestern and Notre Dame were entered; Big Ten champion Michigan was the pre-tournament favorite.

Players were forced to play with old or refurbished golf balls. The war effort restricted the use of rubber, and no new golf balls had been manufactured in over two years. Synthetic balls were still years away.

The Inverness course would be a stern test for the collegians. The Donald Ross design had previously proved its mettle, hosting the 1920 and 1931 U.S. Open Championships.

The team championship saw the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame pull an upset for the team title when Bob Terry made a par at the last hole. Notre Dame’s 311 total was one better than the University of Minnesota; Michigan was third at 318, followed by Ohio State (327) and Michigan State (344). Jimmy Jackson of Washington University in St. Louis took medalist honors with a two-over-par 73. Notre Dame, coached by legendary coach, Father George Holderith, would celebrate its only national championship in golf after six top-four finishes in the preceding 13 years.

Match play began on Monday afternoon, with temperatures rising into the 90s. The euphoria for the Irish faded quickly, as only two of their 5 qualifiers (John Fitzpatrick and Tom Hanlon) survived the first round. Most of the top players advanced: medalist Jimmy Jackson; the Big Ten champion, Johnny Jenswold; Robert Seyler of North Carolina; and Arnold Page, a Toledo native playing for Cornell.

The defending men’s champ was Wallace Ulrich of Carleton College in Minnesota. In 1944, he was an aviation student in the 2612 AAF Base Unit at the University of Toledo. Originally thought to be unable to play because of his studies, he was a late entrant. He qualified for match play but couldn’t play on due to his classroom duties.

Tuesday saw a continuation of the high temperatures, and some exciting golf. Jackson beat Notre Dame’s Fitzpatrick in the morning round 2 & 1. But he ran into a red-hot Louis Lick, a 20-year old medical student from the University of Minnesota, in the afternoon. Lick had beaten Notre Dame’s Hanlon in the morning 8 & 7, and then needed only 13 holes in drubbing Jackson 6 & 5. Lick was 3-under par for the holes he played against Jackson.

Jenswold had an easier run, beating teammate Paul O’Hara 5 & 3 in the morning, and defeating James Harris of Northwestern University 8 & 6 in the afternoon. Seyler and Page both suffered second round losses.

Wednesday saw the semi-finals and finals played in blistering heat, with temperatures topping off at 98 degrees. Louis Lick continued his stellar play in the morning with a 6 & 5 victory over Tom Messinger of Michigan. Johnny Jenswold beat Henry Ramplet of Baldwin-Wallace, a surprise semi-finalist, 3 & 1.

The finals provided some of the best drama of the tournament. Lick raced out to a 3-hole lead with only four holes to play. But Jenswold, playing for Michigan while studying as a naval trainee, won 15 and 16. The players halved 17, and a half at 18 was enough to give Lick a 1-up victory. Lick’s total was 76, while Jenswold shot 77.

Read more...

The third U.S. Open held at Inverness Club weathered a couple of storms—and the inevitable playoff.

The first squall to hit the 1957 U.S. Open came early on Friday, during the first round. High winds from Lake Erie caused trees to bend and tents to blow over the fairway and rough - play was suspended.

Few were aware of the presence of a chubby-cheeked, blonde haired, seventeen-year-old amateur from central Ohio—Jack Nicklaus, playing in his first U.S. Open. Nicklaus, considered by many to be the games’ greatest player of all-time, recalled that he birdied the first hole and pared the second before fading to rounds of 80 and 80. He missed the cut.

After the first two days of play, two names were at the top of the leader board—Dick Mayer and Billy Joe Patton. Experts didn’t expect either of them to stay there. But Mayer’s game stood up as another U.S. Open at Inverness produced an Iron Man or, perhaps, a Fiberglas Man. Appropriately enough, all of Mayer’s clubs were shafted in a relatively new product--at least as it applied to the world of golf-- called Fiberglas, a product of the Toledo-based Owens-Corning Corporation.

Mayer, after his second Saturday round, carding a 70, had eliminated the sentimental favorite, Jimmy Demaret from title consideration. It appeared so conclusive that Mayer went to the press tent and submitted to a champion’s interview. But, defending champion, Cary Middelcoff was still on the course, roaring back from an eight shot deficit to tie Mayer, with a twelve-foot putt for birdie on eighteen, shooting 68 and 68 on Saturday, the final day of regulation play. Sunday’s, eighteen hole playoff was anti-climactic. Middelcoff never seriously contested Mayer, who won by six strokes to win the 1957 U.S. Open, his only major championship.

Read more...

In 1973, the world’s top amateurs roamed the Club’s fairways and greens, as Inverness hosted its only U.S. Amateur Championship. This event was so historic because after an eight-year interlude, during which the United States Golf Association broke with tradition and held its Amateur championship as a stroke-play event, the tournament at Inverness returned to match play. It was the format that crowned Bobby Jones, Francis Ouimet, Chick Evans, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, and so many other greats through the years.

The 1973 Amateur also featured, for the first time in a number of years, all twenty members of the combined American and British Walker Cup teams, which had faced off a week earlier at The Country Club, in Brookline Massachusetts.

As the brackets developed, a dream pairing for the finals seemed likely. Two American defenders, Bill Campbell and Marvin (Vinny) Giles III had advanced to the semifinals. Two youngsters, neither of whom had competed in the Walker Cup, neither of whom had U.S. Amateur pedigrees, and neither of whom was considered a formidable match play competitor, stood in the way of that dream pairing. They were a study in contrasts: law-student David Strawn was 6’2”, 170 pounds and Craig Stadler was 5’10”, 205 pounds, and with mutton-chop sideburns. In the years to come, Stadler would lose the sideburns, but not the girth becoming a popular golfer on the PGA Tour, acquiring the colorful nickname “Walrus.”

Stadler’s Saturday began with a quarterfinal pairing against the reigning British Amateur champion, Dick Siderowf. The 20-year-old from La Jolla, California ended Siderowf’s hopes of becoming just the fifth golfer ever to capture both the British and American amateur titles, in the same year. Giles, Campbell and Strawn also survived morning matches to complete in the semifinal field; however, Stadler ambushed Giles, 3 and 1, while Strawn humbled the 50-year-old Campbell, 6 and 5, after taking a seven-up lead at the turn.

Stadler’s hunger for victory was still evident the next day as he took a 4-up lead after nine holes and scored a 6 and 5 win over Strawn in the 36-hole championship match. The winner admitted that one of his early goals was to qualify for the Masters; in those days, invitations to play at Augusta National were issued to the eight U.S. Amateur quarterfinalists.

Read more...

The 1979 Open offered little drama, compared to the three previous U.S. Opens held at Inverness. Each of them had produced great theater, from the Bobby Jones-Harry Vardon pairing in 1920, to the marathon playoff in 1931, to a hodgepodge of circumstances in 1957, that included Ben Hogan’s withdrawal, Jack Nicklaus’s little-noted debut, a violent electrical storm, and a playoff in stifling heat.

Hale Irwin opened with a 74. He limped home in the final round with a double-bogey, bogey finish that capped a final-round 75, holding on to victory by two strokes. No particularly memorable shots, no gut-wrenching collapses, no real drama.

The 1979 U. S. Open, for better or worse, is remembered mostly because of a tree. George and Tom Fazio designed the 528 yard 8th-hole to be a classic, three-shot, par 5-hole. The Inverness Burn slices across the fairway beyond the landing area. It has five tough and deep bunkers in the proximity of the green.

Lon Hinkle saw the hole differently. He discovered during practice that nothing prevented a player from hitting a tee shot through a narrow opening onto the adjacent 17th fairway, then lofting a long second shot over trees onto the eighth green, a shortcut that cut about eighty yards off the intended track. After several other players used the same shortcut, the United States Golf Association and the tournament called an emergency meeting, even before the first round had ended. Concern for the safety of the gallery and the golfers playing the seventeenth, they considered placing substantial bushes into play, blocking any access to the seventeenth fairway. Or, a tree could be planted overnight to the left of the tee box to plug the existing gap. The latter was the alternative chosen.

Wilber Waters, the fourth of eight superintendents in our Club’s history, was charged with finding, transporting, and transplanting an appropriate tree. Work had been completed by 5:30 a.m., with the planting of a 25-foot Blue Hills spruce which stood looking a bit scraggly and very out of place.

That, however, wasn’t the end for the eighth hole in the tournament’s spotlight. During the third round, Irwin made birdie at that hole. His drive hit a tree and bounced back into the fairway, and his second shot landed in fairly severe rough. Irwin’s third shot was skittering across the green, heading for the gallery and serious trouble, when it clipped the flagstick and stopped some five feet from the cup. He putted-in for birdie. Irwin knew by late afternoon Sunday that the difference between a birdie and bogey at the eighth hole during the third round was the cushion needed for his two-shot victory.

Read more...

Some golfers are remembered for a single, historic shot. Most golf fans would agree that Bob Tway will forever be known for the shot from the greenside bunker in the 68th PGA Championship. The smooth-swinging Tway had stripped playing partner Greg Norman of a four stroke lead in the previous eight holes, and drove into heavy rough on the par-4, 354-yard, eighteenth hole. Tway's 9-iron approach from a downhill lie caught the right-front, greenside bunker. Norman, meanwhile, lofted a 123-yard wedge approach to the fringe of the green.

The green sloped away from Tway, who stepped into the bunker, swung and floated the ball about a foot onto the putting surface. Shocking Norman and the golf world, the ball rolled into the cup. Tway leaped up and down in the sand like a schoolboy, pumping his fists. Norman, trying to regain his composure, chipped 10 feet past the hole. He finished two strokes behind Tway, who became the first player in modern history to win the PGA Championship with a birdie on the 72nd hole. His 8-under-par 276, also made him the first to post a sub-par, 72-hole total, in a major championship at Inverness Club. Tway went on to be named the PGA Player of the Year, finishing the season with four victories.

Read more...

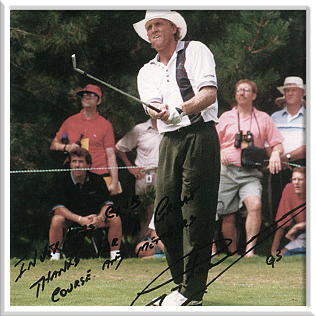

During the final two rounds of the 75th PGA Championship, historic Inverness Club offered a leader board that became a "Who's Who" of golf. While some players, particularly long-driving 1991 PGA Champion John Daly complained of tight fairways and tiny greens, Paul Azinger paid attention to former PGA Champion and Inverness Club professional, Byron Nelson's advice earlier in the week; when at Inverness, play for the middle of the greens. Azinger strung together four birdies in a row in the final round, shooting a 12-under-par 272, tying him with Australian Greg Norman, the hard-luck runner-up at Inverness, in the 1986 PGA Championship.

Norman had a chance to avoid the tie in the regulation 72 holes, but his 10-foot birdie attempt grazed the hole. The twelfth playoff in Championship history began on the Inverness signature 357-yard, par-4 18th hole. Again, Norman missed the birdie putt. This time, the ball spun around and away from the cup. Moving to the par-4 10th hole, Norman fired a wedge shot 30-feet above the cup and Azinger pitched to within eight feet. Norman left his birdie attempt four feet above the cup and Azinger missed, grazing the cup with his putt, before tapping in for par. Norman carefully studied his par putt, but again the ball grazed the cup and spun out. The Australian-born Norman became the second player in history to lose playoffs in all four major championships. For Azinger, it was his first major championship.

Read more...

The premier event in senior golf in 2003— the 24th U.S. Senior Open — became the eighth major tournament hosted by Inverness in its 100 years of rich golfing tradition. Each of the first three days produced a new leader. The excitement was unforgettable. Tom Watson fired an opening round 66, becoming the first golfer ever to lead the initial round of both the U.S. Open and the U.S Senior Open, in the same year. Vincente Fernandez shot a second round 64, one shot more than the competitive course record Vijay Singh shot in the 1993 PGA Championship. Bruce Lietzke’s third round 64; established a four shot lead going into the final day. Overcoming bogies on seventeen and eighteen, at the conclusion of play on Sunday, Lietzke had won his first career major championship, in this, his 53rd major championship appearance, shooting two over par for the day. Only Lietzke (-7), Watson (-5) and Fernandez (-4) finished under par and only the thirteenth hole, a par-5, played under par for the tournament.

Making his debut at Inverness in 1957, golf legend Jack Nicklaus made his last Inverness appearance, at the 2003 U.S. Senior Open. He finished nine over par, tied for 25th place. Here is an excerpt from his post tournament interview:

Q. Do you wish you had another crack at it (Inverness), one more crack?

JACK NICKLAUS: No, I have had enough cracks at this golf course. I finished up -- this is the last time I'm going to play this place. That's fine. I never played well here. I said that at the beginning of the week. I always had trouble with

it. It's not my style of golf course from the way I play golf. It's a golf course that you really have to grind it out, not hit it long, hit it very straight, chip and putt very well for four days. Not that I don't like it. I like it. It's

just always been very difficult for me.

Read more...

The 2009 NCAA Championships featured a new twist with the team champion determined via match play, the first time the winner hasn’t been awarded by total strokes since 1965. The top eight teams after 54 holes of stroke play advanced to match play with the quarterfinals and semifinals being held on Friday, May 29 and the championship held on Saturday, May 30. During the match-play portion of the championships, each match will be worth one point with all five players participating. The first team to win three points within the team match will advance or, in the case of the championship match, be declared the national champion.

The Aggies won the NCAA title in a thriller.

Senior Bronson Burgoon watched as his Pro V1 sailed into the sky above Inverness Club’s 18th hole and dropped down on the middle-right portion of the green, on top of a ledge sloped down to a tucked-left pin position. The second he saw the ball begin rolling left, right about the same time the fans surrounding the 18th green started screaming, Burgoon lost it.

How else to react after hitting the shot of your life – as Burgoon saw it, a 120-yard 18th-hole approach from scraggly rough to “about 4 or 5 inches” for a chance to end his deciding match with Arkansas senior Andrew Landry and win his Aggies their first NCAA Championship? Especially after standing on the 14th tee about an hour earlier with a 4-up lead only to miss four consecutive fairways and greens and lose four consecutive holes.

Just like that, euphoric turned to historic. All factors considered, Burgoon’s shot will go down as one of the best in college golf history.

Read more...

The 32nd edition of the U.S. Senior Open became the ninth major hosted by Inverness Club. The event was hampered by weather conditions. The Toledo area received heavy rains and winds the Friday and Saturday before play started. It rained again during Round 2. As a result, the greens were sticky, allowing many of the players to post scores below par.

Olin Browne dominated the course and spent three rounds at the top of the leaderboard. Providing ample competition for the purse were Mark O'Meara and Mark Calcavecchia. On Sunday, the weather and course conditions improved and gave all the competitors the challenge they so richly desired. Browne gutted out an even-par 71, draining a 28-foot birdie on the 72nd green to finish at 15-under-par for a three-stroke victory. He became the first wire-to-wire winner of the championship since Dale Douglass in 1986. A true highlight of the event was the hole-in-one at the third hole, achieved by D.A. Weibring in Round 2. The cheering crowds could be heard throughout the course.

Read more...

When Preston Summerhays found himself trailing in the 36-hole final of the 72nd U.S. Junior Amateur Championship at historic Inverness Club, he didn’t panic. Instead, he drew from his experience the previous day, when he rallied on the back nine to overcome a pair of deficits.

Summerhays was 3 down to No. 19 seed Austin Greaser after 11 holes in the quarterfinal round, and 2 down after seven holes to Thomas Pagdin in the semifinals. He went on to win 5 of the last 7 holes against Greaser, and 6 out of 7 against Pagdin, employing a similar philosophy each time.

“My mindset was just to keep on playing,” said Summerhays, who also edged 2018 runner-up Akshay Bhatia in the Round of 16. “[Pagdin] had a good first seven holes, and I knew that he’s human. He was going to make some mistakes. I just tried to stay patient.”

When he trailed Bo Jin, of the People’s Republic of China, by three holes late in the morning round of the final, Summerhays kept his cool despite the steamy conditions and won the 17th and 18th holes with birdies to enter the lunch break trailing by just one.

A few hours later, after Summerhays had completed his third straight comeback to claim the Junior Amateur trophy, the club presented him with the flag from the 17th hole as a fitting memento. His performance on the 489-yard par 4 made the difference in his 2-and-1 victory.

In the morning 18, Summerhays had purposely hit his drive on the dogleg-left hole down the adjacent 16th fairway, then knocked a wedge to 35 feet and drained the right-to-left curling putt. In the afternoon, Summerhays hit “the shot of his life,” according to his father and coach, Boyd, to set up a match-clinching birdie that also gave him a berth in the 2020 U.S. Open Championship at Winged Foot Golf Club.

“I don’t even know how to explain how it felt,” said Summerhays, 16, a Utah native who now lives in Scottsdale, Ariz. “It’s just one of my goals being accomplished.”

Summerhays seemed to have taken control as the seesaw match turned to the final nine. He birdied the par-4 10th and 11th holes to assume a 2-up lead, his largest of the day. His lead was reduced to 1 up when he bunkered his approach on the 13th hole and took a bogey. But he retained the lead on the 16th hole as Jin three-putted and Summerhays saved his own bogey from 15 feet after stubbing his first chip shot.

Summerhays again opted to play down the adjacent 16th fairway when they got to No. 17, but he pushed his tee shot and left himself in the rough between the fairways, with a large tree blocking his view.

“It wasn’t a terrible lie, and I had 174 [yards] to the pin,” said Summerhays. “Going downwind, downhill, it really didn’t play 174, it played 145 to the front edge. I was like, I could get a pitching wedge over that tree and land it front edge and roll it back. I hit it great and it ended up going to 8 feet.”

Jin then left his approach on the front of the green, skirted the hole with his long birdie try, then missed the comebacker. With two putts for the win, Summerhays made birdie.

“That's just a shot of a lifetime at the right time in the biggest tournament,” said Boyd Summerhays, who coaches several PGA Tour players, including world No. 14 Tony Finau, and walked the matches with his son. “He'll never forget that and it'll give him confidence when he's in a tough spot.”

Read more...

The American team, led by captain Pat Hurst and Nelly Korda, the top-ranked player in the world, was heavily favored. Nearly all of the 130,000 spectators who lined the course during the weeklong event enthusiastically supported Team USA. Travel restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic significantly limited the large number of international travelers who normally attend this event. Nevertheless, the attendance figure for the week set a Solheim Cup record.

The European team, despite their distance from home and the limited number of their supportive fans, gathered a two-point lead heading into the singles matches, a lead which withstood several threats from the American team. Finland’s Matilda Castren holed a putt on the seventeenth green to clinch the win for the Europeans, 15–13. Ireland’s Leona Maguire led Europe with a 4-0-1 record. Victorious captain Catriona Matthew lifted the Solheim Cup trophy for the second time in row.

Read more...